Frank RodickNos cuenta su experiencia en la EAF

1- How was your experience exhibiting in Buenos Aires ? I’ve had several exhibitions in Buenos Aires and they’ve always been a wonderful experience. I’ve exhibited at festivals all over the world and the Festival de la Luz is one of the best. The audiences are enthusiastic and knowledgeable. The organizers are efficient, helpful, and they work very hard to make us all feel welcome. I always feel privileged to exhibit here.

2- Did you have any special interest in the city or in the Festival that made you come? Well, first of all, I’ve always considered Buenos Aires to be one of the world’s great cities, a place with a unique history, architecture, a special cultural atmosphere. So when I was first invited to exhibit in 2002 by Elda Harrington I didn’t hesitate to say yes. Since then, I’ve exhibited and visited several times. That's deepened my relationship with the city and certain special people. My relationship with Elda Harrington, with whom I’ve worked closely, is very important to me. I love working with Elda — there’s no one more professional in the photographic art community. She's imaginative, totally efficient, very caring, a leader who makes things happen, and a person of complete integrity. So I feel a very strong allegiance and loyalty to the Festival and to her. It’s professional but it’s also personal.

Regarding the audiences in Buenos Aires, one of the things I enjoy most is that they bring a very passionate, emotional relationship to art. I think that's often lacking in the North American arts community, which can be more detached and distant. I know this sounds like the Latin versus Anglo-Saxon stereotypes, but, still, I feel there’s truth to it. There’s also less inhibition and judgementalism in Argentine audiences, particularly when it comes to themes of sexuality and death. I appreciate that as well, especially since these themes run through my work.

I’ve also had wonderful experiences teaching and lecturing in Argentina, largely because of opportunities through Elda’s school. I enjoy doing this, but all the more so when the students and audience members are so active and engaged, which they always seem to be.

3- What is photography for you? I consider myself an image maker, who happens to use photography because it’s a medium that I grew up with and feel comfortable with. I see it as as a complex tool for making images that mean something to me and, hopefully, carry meaning for my audience. I don’t see it as a medium that’s any more insightful than any other in the visual arts. That’s all up to the insight, commitment, and skill of the artist who uses photography. But it is a powerful tool, one that’s become even more powerful with digitization, which gives it a lot of depth and possibilities. Photography, like any other visual arts medium is a way of saying things without verbal or written language (although it can include those elements). As someone who loves the written word, I’m also very interested in a language in which I can explore and express things that I can’t with words alone.

Speaking of digital photography, it, like any medium, is only as effective as the artistic foundation it’s built on, which is the difficult part. Chuck Close once said that photography is the easiest medium to become technically expert in and the most difficult in which to develop an artistic vision. I think that’s true, and even more so with digital photography. A bad artist using digital photography is like a less dangerous version of a chimpanzee with a machine gun.

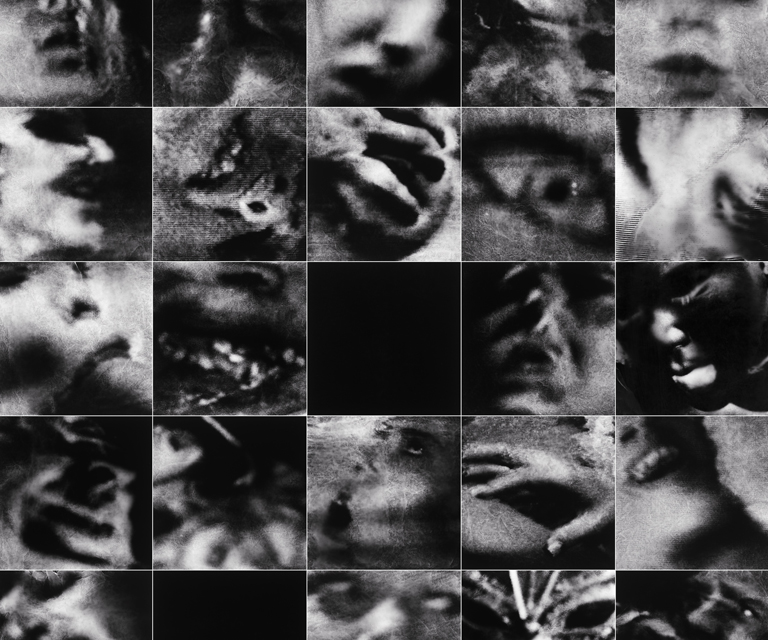

4- Which, would you say, is the most important issue in your work? I suppose it’s fair to say that I like the big themes — sex, death, isolation. I’m a little uncomfortable saying that without more context because it runs the risk of sounding a little pretentious. Then again, who cares, since any artist that really wants to do something with their work runs the risk of pretentiousness. In any case, my themes aren’t a matter of deliberate calculation. My method for working is pretty simple on one level: I just start with the most important thing to me at the present time. And that always involves conflict and tension of some kind. I move from there, exploring, experimenting, getting lost, going up paths that go nowhere, and — sometimes — finding a path I want to follow and get into more deeply. Inevitably this leads back to those same big themes — not so surprising, when you think about it — albeit in different ways. So, when my mother died a few years ago after a long and awful illness, it seemed natural to try making pictures about that. But of course what happened was that what I started with — my mother’s life and death — became something else: a meditation on on my relationship with her and the great, unfortunate, distances that exist between people, as well as, ultimately, my own life and death.

5- Which message would you like to leave to the argentine students of photography? It would be easy for me to give you some platitude like “be true to yourself, follow your own path,” that sort of thing. But the thing I like to share with my students is that it’s really worth considering doing work based on the most important thing in your life, what’s most emotionally pressing. And that’s a lot harder to do in practice than it sounds. It’s a lot of work. Sometimes, often, it’s hard to become conscious of what’s most important, most pressing, to you because much of what we do psychologically is defend precisely against being conscious of that. So it’s hard work — even psychologically dangerous work — to go there. And once you start becoming aware of it, you have to figure out what to do with it. Not everyone is ready to do that and it’s not my place to dictate that someone go there. But I find that’s where the real gold is. The other stuff can be interesting — and photography’s full of interesting work, which tells us about all kinds of different things — but the amazing stuff is usually deeper. Of course, the risk of failure is also greater. The risk of pain and disappointment too. As the saying goes, "Who seeks hard things, to him is the way hard.”

The other thing I’d say — and this is really related to the first point — is to resist the temptation to use your work to try to prove how smart you are, or what a good person you are. I mean, we all care to some extent about what others think of us (I know I do) and it’s pretty natural to want to others to think we're intelligent and good people. But when that’s the driving force behind making art — and it’s more of a driving force than a lot of artists are willing to admit — the results are pretty awful ultimately, boring, lifeless. It isn’t that any of us have to obliterate those desires and inclinations — like I said, they tend to be there, in greater or lesser degrees — but if we’re sufficiently aware of them, we can make sure they don’t dominate our work, that our work becomes more of an expression of our more intimate selves. There’s nothing wrong with proving that you’re intelligent or good — it’s just better to do it in some other area of your life.

Of course there’s lots more I could say, there’s another point I’d like to make, namely, that I think students should spend the time it takes to become expert in their craft. It sounds obvious, but with digital photography especially, I’m seeing a lot of people who leave so much work up to their printers that I think they’re losing the creative opportunities that come with being really immersed and expert in your own craft. Sometimes it’s as if they’re more directing the making of the image than making the image themselves. For some people, that was a problem with traditional darkroom photography too. There are so many times that, through the process of wrestling with what amounts to a technical problem, I’ve discovered something that has creative, aesthetic value.

The final thing is that if you ever want to have hope of making a substantial set of good pictures — and I use the plural deliberately because it’s become a lot easier for people to make an outstanding picture or two, but that doesn’t make an artist — if you have that hope, you quite simply have to work a lot. Work like a dog. Make a lot of images. Most of them will be bad, but that’s normal. The next best thing to a good picture is a bad picture because that helps teach you what to do next. The worst thing is sitting around, thinking too much, and not making pictures. Rodin had the best advice for artists: Il faut travailler. You must work. 6- Do you want to add something else?

One thing I’d like to say is that people should remember what a major undertaking something like the Festival de la Luz is, and how so many people put in unbelievable amounts of work and give up so much of their personal time and energy to make it happen for all of us. And I think that means that the rest of us in the arts community — artists and non-artists — should do what it takes to support the Festival as best we can. That can be by helping out in some way, by opening our wallets, by donating our time and energy and whatever else we can give, by working cooperatively and generously, by letting other people know what a great event it is and that it deserves not only their attendance and interest but their support too. It’s hard work being an artist and it’s hard work putting together great arts events like the Festival. I want the people who do that — and do it well — to know that I don’t take them for granted, that I want to support them, and that they’ve more than earned my affection.